me lu ju'i lobypli li'u 8 moi

For a full list of issues, see zo'ei la'e "lu ju'i lobypli li'u".

Previous issue: me lu ju'i lobypli li'u 7 moi.

Next issue: me lu ju'i lobypli li'u 9 moi.

Front Matter

Copyright, 1989, 1991, by the Logical Language Group, Inc. 2904 Beau Lane, Fairfax VA 22031-1303 USA Phone (703) 385-0273 lojbab@grebyn.com

All rights reserved. Permission to copy granted subject to your verification that this is the latest version of this document, that your distribution be for the promotion of Lojban, that there is no charge for the product, and that this copyright notice is included intact in the copy.

Ju'i Lobypli Number 8 - March 1989 Published by: The Logical Language Group, Inc. 2904 Beau Lane, Fairfax VA 22031 USA (703)385-0273

This publication is the articles section of Ju'i Lobypli, the quarterly publication of The Logical Language Group, Inc., known in these pages as la lojbangirz. la lojbangirz. is a non-profit organization formed for the purpose of completing and spreading the logical human language "Lojban". The newsletter section of Ju'i Lobypli is now separately published under the name le lojbo karni(bearing issue number 8 to correspond with this JL issue). You should already have received that issue by the time you receive this.If not,and it isn't received within a week or two, please write and let us know.

le lojbo karni was distributed to over 400 people, including all JL subscribers. Some 275 of you will receive Ju'i Lobypli.

HELP!!! OUR FINANCES ARE IN REALLY BAD SHAPE. PLEASE HELP BY BRINGING YOUR BALANCE POSITIVE (OR MORE). PLEASE, DON'T PROCRASTINATE.

In over two weeks since LK8 went out, we have received almost no responses or income. Our bank account will be down to about $500.00 after this issue goes out, and we need $400.00 alone just to file the 501(c)(3) papers to get our non-profit status. I've had to give up on getting some professional accounting help on the filing, and on better organizing our business finances; we can't afford it. We are committed to publishing LK9 by May 1, in order to make sure that those coming to LogFest know the plans, and we don't have the money right now.

We also have put off making cassette tapes for a few more months, partly to ensure they are of good quality, partly because we cannot afford them in addition to flash cards and other inventory items that we need more immediately. In preparing for the influx of new people we hope to receive in response to our new advertising efforts, we are spending some $1000 per month to build our publication stock and prepare new products of quality.

Finances will probably continue to be tight at least until after the textbook is finally published, and right now we don't have the several thousand dollars that will be needed to bulk publish the textbook. We (Bob & Nora) can't finance it - our contribution has been my free labor in lieu of my getting a paying job that would almost certainly affect the schedule. The result of insufficient funding will be that the textbook may cost much more than it should.

Lojban is done; people are learning it. To make it succeed, we must have further support. I believe that la lojbangirz. has done its part of the bargain in keeping Lojban moving. Have you contributed your share?

Potential donors please note: we have not received IRS approval for Section 501(c)(3) status, which will officially allow your donations (not contributions to your voluntary balance) to be tax-deductible. We hope to have such approval by the end of the year. We are operating in accordance with that section, and your contributions now should be deductible if approval is obtained later, although there is always the possibility of disapproval. You may, if you wish, make your donation contingent on our getting such approval. We will inform all donors at the end of the year as to the status of deductibility of their gifts. We also note for all potential donors that our bylaws require us to spend no more than 30% of our receipts on administrative and overhead expenses, and that you are welcome to make you gifts conditional upon our meeting this requirement.

Your Mailing Label

We've simplified your mailing label, and now report to you only your current mailing status, and your current voluntary balance including this issue. Please notify us if you wish to be in a different mailing code category. Balances reflect contributions received thru 26 March. Mailing codes (and approximate annual balance needs) are defined as follows:

Level B - Product Announcements Only Level 0 - le lojbo karni only - $5 balance requested Level 1 - le lojbo karni and Ju'i Lobypli - $15 balance requested Level 2 - Level 1 materials and baselined/final products - $20 balance requested Level 3 - Level 2 materials and teaching materials as developed - $50 balance or more

Contents of This Issue

The bulk of this issue is the enclosure draft lesson 1 of the textbook, and the outline of the rest of the book. The draft lesson has been through two revisions, but we welcome your additional comments. The outline is approximate; we are finding it necessary to move things around a little as we teach the first class. Some of the lessons are taking a little longer than the estimated 3 hours, though part of this may be due to it being new material and own inexperience in teaching it. The textbook should cover all material in the outline in any case.

Other Contents:

Machine Translation and Lojban - Patrick Juola

le lojbo se ciska

Dave Cortesi's Proverb

Dialog from Evecon Presentation

'The Quest'

'99 Bottles of Beer'

lei lojbo

Letters and Responses

Dave Cortesi on Lojban's Design

Rory Hinnen's tanru

Doug Loss Responds to my JL7 Comments

Note on Materials from Ralph Dumain

We indicated in LK8 that we would be printing submittals from Ralph Dumain. Ralph submitted a good quantity of material for inclusion in this and later issues, including discussions of several issues relating to the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis(SWH), and a bibliography on SWH. For space and editorial reasons, we cannot print any of it in this issue.

Given the depth and scope of the material, which is outside of my expertise, I am having pc (John Parks-Clifford) review the material for technical accuracy and possible response. Ralph's material has been provocative in the past, and Jim Brown (among others) has taken personal offense. The new material has a mixture of information and opinion, and I want readers to be clear as to which is which. Apparently SWH is controversial on a philosophical, sociological, and political basis, in addition to the linguistic relevance it has to the Lojban project. We like the idea of Ju'i Lobypli contributing to the intellectual debate on SWH and other issues; we want that contribution to be balanced and informative. With a quarterly publication, we have a risk of a drawn-out non-productive debate that will be confusing to new people who come into the middle of it.

Our intent is to use Ralph's articles as a focus for one of the discussion sessions at LogFest, and then to print his contributions and a report on the discussions in the following JL issue (#10).

The material on SCRABBLEtm for Lojban will be delayed until next issue.

Next Issue

Next issue will include a reprint of a recent article in "The Mathematical Intelligencer", by Professor Robert Strichartz of Cornell University, on the need for 'An International Language for Mathematics'. We will discuss how Lojban meets the criteria raised by Dr. Strichartz and others, and perhaps go into a little of our design in this area. While previous versions of the language have addressed mathematical expression, Lojban is the first version of the language to include a comprehensive solution to what is called the 'MEX' problem. We also hope to present some discussions on Lojban's usefulness as a specialpurpose language for mathematics, philosophy, logic, and computer applications. We invite your contributions on these topics, including responses to Patrick Juola's letter below. The subject will also be a topic at LogFest.

Machine Translation and Lojban

by Patrick Juola

[Patrick Juola is a consultant with the Systems Architectures Research Dept., AT&T Bell Laboratories, and president of Dorick Industries of Baltimore. His current research interests include knowledge representation and logic programming. For correspondence, contact him at patrick@vax135.att.com or HO 4G-628, AT&T-BL, Crawfords Corner Rd., Holmdel NJ 07733 (or write to us at la lojbangirz.)]

There is an apocryphal story about an early (1952) automatic English/Russian translation project. A visiting senator asked to see the machine work, and gave it the phrase Out of sight, out of mind to translate. The senator, however, knew no Russian, so the (Russian) phrase was sent back through for the senator to read. The new version read Invisible idiot. Historically, there have been three main methods of machine translation. The simplest, earliest, and least functional can be called direct translation. These machines operate like a first-year language student; looking up a particular word or phrase in a dictionary, writing down the corresponding foreign word (or phrase), then performing simple transformations (e.g., moving the verb to the end in German) to make the result more grammatical. Like a first-year student, this requires almost no "understanding" of the language in question, and (like a first-year student) the translations produced tend to be very bad. The Georgetown Automatic Translator was an early machine of this type -- started in 1952, it became operational in 1964 and was actually in use until 1979 (and its "daughter," SYSTRAN, is still commercially successful). With the improvement in machine capacities (and over thirty years to correct mistakes), SYSTRAN does produce acceptable translations. At the very least, direct translation provides a yardstick against which to measure more sophisticated projects.

The majority of the modern MT projects[1] use what is called the transfer approach. Translation is divided into three phases: Analysis, Transfer, and Synthesis. In analysis, the sentence, phrase, or paragraph to be translated is parsed into what is called a "parse tree," a detailed description of its syntax. At the same time, the meaning of the sentence is analyzed into a semantic network, describing the meanings of the individual words and the relationships among them. This is obviously a much harder project than merely looking up words in the dictionary but is frequently necessary to get an accurate translation. For example : The city council denied a permit to the women because they advocated violence. Who advocated violence, the council or the women? (In French, they would be translated differently, because of the genders.) The transfer involves changing the parse tree in ways specific to the source and target languages (the actual "translation", usually requiring structural changes as well as dictionary look-up), while the synthesis is reverse parsing.

The transfer method tends to produce the most accurate translations. Because of its firm theoretical basis in linguistics, it tends to be robust, amenable to analysis, and easy to update/modify. On the other hand, it is expensive. The amount of semantic information required per word is usually extensive, and the transfer functions tend to be complex and expensive to write. The TAUM project[2], for example, reported costs of $35-40 (Canadian) to develop each lexical entry (word, to non-linguists), as well as a cost of 16 cents/word for the actual translation and post-editing. (Comparable costs for human translation were about 12 cents/word.) Two sets of transfer rules must be written for each pair of languages. For the seven- language EEC, this would mean 42 different transfer functions. With the addition of Spain and Portugal, nine languages and 72 functions. And so on...

The final approach (and the one where Lojban would be most useful) is termed interlingua. Rather than writing specific transfer rules, one can instead translate into "linguistic universals," where the meaning and structure of the internal representation are independent of the language from which they were derived. This method is the closest to true "machine understanding" of language. Translation is then a two-step process; translating into the interlingua, then translating into the target language. This approach was pursued by CETA[3] for ten years between 1961-71. It is obvious that this method is easily expandable to multiple languages, since the interlingual representation can serve as a source text for any number of translations. (Only 14 functions are needed for the EEC, for instance, and 18 when Spain and Portugal are included.) There are several disadvantages, however.

The main problem is the design of the interlingua. Ideally, it should be capable of representing any human thought, with all its connotations and associations. The vocabulary required would stagger almost any programming team. For example, the verb to wear has four different translations in Japanese, depending upon what one wears. A programmer would not only need to be aware of this fact, but also be able to express what distinguishes the translations apart, in a form that the computer can understand. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that the computer does not "translate" using an interlingua; instead, it "retells" the source text in the target language. In poorly designed systems, this can lose important syntactic details (such as the passive voice), but even in good systems, style and connotations can be subtly (or unsubtly) affected. (In contrast, a transfer approach can use cognates and similar items and avoid this problem.) Since the computer must be able to generate an interlingual representation, if for any reason the parser fails (ungrammatical sentences, specialized jargon or acronyms, typographical errors, and simple programmer or hardware errors can all cause parser failure), there can be no translation, where a transfer or direct approach can at least generate a word-by-word or phrase-by-phrase translation. Finally, it is obvious that the computer must perform two translations, with corresponding intelligibility loss in both.

Upon examination, Lojban appears to be an ideal or near- ideal interlingua. It is independently motivated to be an artificial language "capable of representing any human thought," although possibly with associations and connotations of its own. The actual vocabulary of Lojban is small, with the great majority of the "words" being metaphors (comet translates to bisli ke cmalu plini, "ice- small-planet."[4] In this case, one "word" is a four-gismu utterance.) This makes the development, addition, and representation of words much easier, particularly if lexical entries contain property lists (i.e. +/-Human, +/- Animate, +/-Female, etc.) as they do in most modern translation projects. In Lojban, a tanru is defined simply and completely on the basis of its properties ("planet, +Ice, +Small").

Since Lojban has been developed from the world's major languages, cognates may be available for both translations, improving the accuracy of the translations. It still has both the required degree of independence (from existing languages) and a certain amount of freedom from connotations. Finally, the task of generating target text from Lojban should be marginally simplified by the regular structure and high available vocabulary (of tanru) of Lojban.

Since vocabulary and language design problems have been the major stumbling blocks, Lojban could already prove a major asset to an interlingua MT project. The true power of Lojban as an interlingua cannot yet be realized, or even assessed. Computers cannot yet "think" in first- order logic.[5] When this barrier is breached, (and at this point, we have left the realm of engineering and entered science-fiction) Lojban itself may be a computer programming language, making a Lojban-based translator self-programming.

The implications of this are staggering, since at this point the "translation program" would be capable of understanding and learning from anything it read. This could be a breakthrough into true Artificial Intelligence. At the very least, the translator would approximate human abilities in learning languages. When faced with a new word, the computer could ask for a definition (in the source language or in Lojban), then use its knowledge of the language structure to determine how that word should be used. For example, if it received the English word mallet, defined as a small wooden hammer, it would know (since it knows about hammers) that a mallet is -Human,- Animate, and +Noun. It could then use the phrase small wooden hammer in the target language, and if it ever receives the phrase small wooden hammer in another text, it can translate it into English as mallet. Even without the major breakthrough, the fact that Lojban is so structured and unambiguous simplifies vocabulary development. The act of defining a word as a tanru automatically assigns it a place in a semantic network, and this procedure could to a large extent be automated using existing AI techniques. Similarly, the act of translation into an unambiguous language automatically focuses attention on the ambiguities present in the source text, where expert systems or human intelligence can be brought to bear upon and immediately resolve them.

In anything resembling artificial intelligence, there is always a conflict between those who want to "do it right", and those who want to "just do it." Since hardware is both inexpensive and fast, the performance of even bad designs can be quite good. In the long run, however, the problem of language understanding and translation is clearly fundamental to the development of true machine intelligence. Of the three current approaches to MT, the interlingua is clearly the most ambitious, but may offer the best long-term potential for the understanding of human and machine linguistics. Lojban (or a similar unambiguous language) cannot by itself solve the problems of automatic translation (or AI), but indicates an approach that may put the entire problem of machine intelligence on a much firmer footing. If human discourse can be expressed unambiguously and in a fashion that computers can use in their own "reasoning," machine intelligence is easily achievable.

It is interesting to speculate on one apparent limitation of Lojban-based translation. Humor based on ambiguity would be very difficult, if not impossible, to translate, since the ambiguity would have been (deliberately) lost in the interlingua. Is this a real limitation of the translator? How important is ambiguity to human language understanding? This question relates closely to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, if we assume that native speakers of Lojban would have the same language background as a Lojban-based AI. Will native Lojban speakers be able to understand ambiguity at all? These questions must unfortunately remain open for quite some time (barring theoretical breakthroughs, until we have native Lojban speakers), but are important not only to Lojban, but to the fundamental theory of "linguistic universals" and machine translation.

Footnotes

- ↑ See (Goshawke 1987) for a listing of some modern projects. (Slocum 1987) has more detailed (and technical) descriptions.

- ↑ Traduction Automatique de l'Universit� de Montreal, 1965- 1981 (See Gervais 1980).

- ↑ Centre d'Etudes pour la Traduction Automatique, Grenoble, France.

- ↑ Metaphor by Jamie Bechtel and Bob LeChevalier (JL 7, p.29).

- ↑ PROLOG, the best known logic programming language, can only express the "Horn clause subset" of first order logic. It is also neither sound nor complete. This is typical of logical languages where machine performance is a consideration. (Lloyd 1984) has some highly technical discussion of the limitations of logic programming.

Bibliography

Gervais A. (1980). Evaluation of the TAUM-AVIATION Machine Translation Pilot System. Translation Bureau, Secretary of State, Ottawa, Canada.

Goshawke, Walter, et al. (1987). Computer Translation of Natural Language. Halstead Press, NY.

Lloyd, J.W. (1984). Foundations of Logic Programming. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Slocum, Jonathan, Ed. (1987). Machine Translation Systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Wilks, Yorick. (1985) Machine Translation and Artificial Intelligence : Issues and their Histories. Computing Research Laboratory, New Mexico State University, Los Cruces, New Mexico.

le lojbo se ciska

Dave Cortesi's Proverb

[It's great when someone other than Nora or myself writes in Lojban, since it helps convince the rest of you that Lojban is indeed easy to learn and use. It is even better when the contribution comes from someone who has effectively taught himself from the teaching limited materials we have produced so far, and yet is both reasonably correct in grammar and logical in approach. Let Dave's efforts serve as example and inspiration to the many of you that are trying to learn Lojban.

Note at publication: It's also important to point out that I am not that expert at Lojban yet. I found a last minute error and Nora found two more in what I had told Dave was a perfect translation. Oh well. All of our points are minor, and they are common areas for confusion or error. Dave still did an excellent job.]

Dave:

"jdini" came up on Lojflash and reminded me of when, back in TL, somebody was trying to translate proverbs. So I thought I'd try my hand at "The love of money is the root of all evil." I think I got it right but I would like you or Nora to check my work.

After some false starts I decided that the final sentence would be based on "krasi" which means (if I read the implicit part of the word-list correctly) "x1 sources x2", leading to:

(the love of money) krasi ro ka palci

How am I doing so far?

"money" ==> "jdini", but it isn't the object of acquisitive desire; that's insatiable. Loving a particular piece of currency would only be silly; what it's evil to love is: "loi jdini". Right?

But this "love" is not "prami". The sense is of "desire" ==> "djica". And "strong desire", so I used: "carmi djica". And it's the event of that, so for x1 I end up with:

le nu ke carmi djica loi jdini kei

There are so many chances for error in that... is it ANYthing like right?

Anyway, what I had so far was:

le nu ke carmi djica loi jdini kei krasi ro ka palci

but when I pronounced it, it didn't seem to have the right oratorical feel to it. Then it occurred to me that "se krasi" could be read as "x1 arises-from x2", and that lets me elide the "kei", giving:

ro ka palci se krasi le nu ke carmi djica loi jdini

and that is a sentence you can really thunder out as from a pulpit. It has a nice swing to it, and you can practically spit the "jdini" at the end.

Finally I still wasn't happy with "carmi djica". The point of the proverb is not that desire is wrong because it's 'intense', but because it is 'not controlled'. I wanted the sense of "unbridled desire." So there's "control" ==> "jitro"; "jitro djica" should be "controlled desire."

Or would it? I can't quite decide whether that needs a "ke", as in "jitro ke djica" for "controlled type-of desire," or whether the simpler tanru sequence does it.

Anyway, I want the opposite of "jitro", which would be "na jitro" as a bridi but I see it requires "bo" to limit it to one tanru, hence:

na bo jitro (ke?) djica is my unbridled desire. I gather that I could write that "naljitro" I won't take the chance, but "naljitro" (if it really means "unbridled") would be a handy composite to have.

So, final form of "The love of money is the root of all evil." is:

ro ka palci se krasi le nu ke nabo jitro djica loi jdini

Comments from Bob:

Dave's reasoning was impeccable, and was accurate based on the materials he had at the time that he wrote it. He had a significant grammatical error which we didn't notice until preparing this issue; there have also been two minor changes that affected the grammar materials he used to write this.

The error came when he reversed his bridi by conversion with "se". Whereas the "kei" in the "nu" abstraction adequately terminated that sumti in the x1 position, he has not included a terminator on "ro ka palci". The tanru thus continues, absorbing the "se krasi" (The result is grammatical: two sumti with no kunbri, but is not what he wanted to say.) Since he wants to separate "se krasi" as the kunbri for the sentence, he can best do this by marking the start of the kunbri with the separator "cu". There also are an elided "ku" and "kei" at the end of the x1 sumti, either of which would have been adequate for termination in this sentence, but "cu" is the more general solution.

This gives:

ro ka palci cu se krasi le nu ke nabo jitro djica loi jdini

The first change to the grammar is that "ke" is no longer required after "nu" to give 'long scope' to the abstraction; this is the recent change mentioned in LK8. The other is that "bo" is not required after "na" in negating brivla; 'short scope' (of one brivla) on "na" is assumed (this was an error on my part when I wrote the grammar description that he used). On his other questions:

1. "ke" in the middle of the tanru "jitro djica" is permitted but not necessary. "ke" serves only to cause grouping in tanru, and has an implicit 'elidable' terminator "kei" at the end of the tanru. Used in the manner Dave asks about, these 'brackets' group a single term, which has no effect on the tanru or sentence structure.

2. There are no 'official' lujvo or definitions, but Dave's assumption of "unbridled" or "uncontrolled" seems the most logical for "naljitro". "na jitro" is still correct, as well.

Comments from Nora:

The tanru "na jitro djica" probably isn't what you want; it means "not-controller type-of wanter". You probably want "not-controlled", or "na se jitro djica". As a lujvo, this becomes "nalseljitro djica". Bob amends his last point: "naljitro" can't mean "uncontrolled".

She would prefer "loi nu nalseljitro ..." or "lo nu nalseljitro ...". She back translates as "All evilnesses originate from the events of uncontrolled desire for money". Evil isn't caused by specific things you are describing as uncontrolled desires; it is caused by things which are such events ("lo"), or possibly by the mass of such uncontrolled desires ("loi"). This is a semantic choice and not a grammar error; what you choose depends on what you think the aphorism means. Of these two, Bob would go for "lo": "All evilnesses originate from events of uncontrolled desire for money"; if "ro ka palci" were "loi ka palci", then the other could also be "loi": "The mass of evilness originates from the mass of uncontrolled wantings of money."

The corrected expression, including all of our comments, is thus:

ro ka palci cu se krasi lo nu nalseljitro djica loi jdini /ro,kah PAHL,shee shu,seh KRAH,see lo,nu nahl,sehl,ZHEE,tro JEE,shah loi ZHDEE,nee/

Again, these errors are relatively minor. Dave has the right idea. Keep up the good work.

Dialog from Evecon Presentation

The following dialog was used by Athelstan and Bob at the presentation on Lojban at Evecon, New Years Eve. Later that evening, this convention featured the wedding of convention organizers Bruce and Cheryl Evry. Unfortunately, none of us managed to attend the wedding due to our over-active Lojban recruiting efforts, but reports indicated that it wasn't anything to sleep through.

B: coi .Atlstan. xu do ba klama le specfari'i be la brus. .e la cerl.

/shoi .AH,tl,stahn. khu do bah KLAH,mah leh speh,shfah,REE,hee beh lah brus .eh lah sheh,rl./

"Greetings, Athelstan. Is-it-true you will-go to the wedding of the-one-called-Bruce and the-one-called-Cheryl."

"Hi, Athelstan. Are you going to Cheryl's and Bruce's wedding?"

A: cu'i go'i gi'onai sipna

/shu,hee go,hee gee,ho,nai SEEP,nah/

"(Uncertain) The-last if-and-only-not-if (I) sleep."

"I don't know. Either that, or I'll be sleeping."

B: do na banzu sipna ca le prula'icte .ije'i loi specfari'i cu na cinri do

/do nah BAHN,zu SEEP,nah shah leh pru,lah,HEE,shteh .ee,zheh,hee loi speh,shfah-REE-hee shu nah SHEEN-ree do/

"You not-sufficiently-sleep on the last-night. (and-how-logically-connected-this-with-the-bridi) Weddings are-not-

interesting to-you."

"Didn't you get enough sleep last night? Or don't weddings interest you?"

A: ja .i mi cupli'u la .uest. vrdjinias. ca le prula'icte

/zhah .ee mee shup,LEE-hu lah .wehst. vr-JEE-nyas. shah leh pru-lah-HEE-shteh/

"Or. I loop-traveled via-West Virginia on-the-last-night."

"(Non-committally) One or the other. I went to West Virginia and back last night."

B: .uu le zu'o go'i cu tapri'a nandu .i pei do sipna cavi le specfari'i

/wu leh zu,ho go,hee shu tahp,REE,hah NAHN,du .ee pei do SEEP,nah cah,vee leh speh,shfah,REE,hee/

"(Regret!) The activity-of-the-last is tired-causingly difficult. (How do you feel about?) you sleep during-at-

the-wedding?"

"I'm sorry to hear that. You could always sleep at the wedding." (Intended humorously)

A: u'e .a'a

/.u,heh .ah,hah/

"(Humor!) (Expectation!)

"Ha, ha! I expect so!"

'The Quest' ('The Impossible Dream')

from Man of la Mancha Copyright 1965 Andrew Scott, Inc. and Helena Music Corp.

I (Bob) attempted to translate this song and the theme song from 'Man of La Mancha' back in 1980 as my first effort in learning the language. I failed miserably; the grammar was far too complicated for what was presented in the "Loglan 1" book. I visited Dr. Brown (JCB) with my efforts; he was discouraging about my translation attempts and the efforts I had made to learn the language, and I abandoned my then-attempts to learn, though I continued to support the project.

I endeavored to preserve rhythm as well as content in this translation, and can sing it somewhat after a fashion. A glossary of lujvo and a couple of cmavo is given at the end.

le mivmu'i ai mi senva le na se senva ke traji .ije damba le na seldamba ke traji .ije renvi le drikai na selrenvi .ije virklama le virnu na se darsi .ije drari'a le na draselri'a ke traji .ije curve je darno ke prami .ije troci se pi'o le dusta'i ke birka .ije snada le na selsnada mukti .i mi selmu'i lenu jersi la'ede'u .iju mi na pacna .iju du'erda'o .i mi damba mu'i loi xamgu sekainai loi senkai ja depkai .i mi gunta le cevypro ki'u le cevmu'i .aicai .i ganai mi ralte .ai le mukti noika selsi'a kei gi'e ka curve gi mi vreta sekai loi pankai je smakai ca lenu mi morsi .i loi rolremzda ba xagmau ri'a lenu pa prenu noi selckasu gi'e xramu'e bapu troci sepi'o ro leri vrikai lenu snada le na selsnada ke tarci

Glossary

cevmu'i cevni mukti godly motive cevypro cevni fapro god opposer depkai denpa ckaji the property of waiting (pause) drari'a drani rinka to correct draselri'a drani se rinka to be corrected drikai badri ckaji sorrow du'erda'o dukse darno excessively far dusta'i dukse tatpi excessively tired la'ede'u the referent of the earlier sentences mivmu'i jmive mukti life-goal (quest) papkai panpi ckaji peacefulness rolremzda ro remna zdani all-human nest (world) selckasu se ckasu ridiculed seldamba se damba opponent/foe selmu'i se mukti be motivated (by ...) selrenvi se renvi survivable selsi'a se sinma esteemed, honored selsnada se snada achievable senkai senpi ckaji the property of doubt (question) smakai smaji ckaji property of quietness virklama virnu klama bravely-go-forth vrikai virnu ckaji bravery xagmau xamgu zmadu better xramu'e xrani mutce much injured

Pronunciation and Phrasing Guide

.ai mi senva le na se senva ke traji

/.ai mee SEHN,vah leh,nah,seh SEHN,vah keh,TRAH,zhee/

- - / - - / - - / -

.ije damba le na seldamba ke traji

/.ee,zheh DAHM,bah leh,nah,sehl,DAHM,bah keh,TRAH,zhee/

- - / - - / - - / -

.ije renvi le drikai na selrenvi

/.ee,zheh REHN,vee leh DREE,kai,nah sehl,REHN,vee/

- - / - - / - - / -

.ije virklama le virnu na se darsi

/.ee,zheh veer,KLAH,mah leh VEER,nu nah,seh DAHR,see/

- - / - - / - - / -

.ije drari'a le na draselri'a ke traji

/.ee,zheh drah,REE,hah leh,nah drah,sehl,REE,hah keh TRAH,zhee/

- - / - - - / - - / -

.ije curve je darno ke prami

/.ee zheh SHUR,veh zheh DAHR,no keh PRAH,mee/

- - / - - - / - - / -

.ije troci se pi'o le dusta'i ke birka

/.ee zheh TRO,shee,seh pee,ho,leh du,STAH,hee keh BEER,kah/

- - / - - - / - - / -

.ije snada le na selsnada mukti

/.ee zheh SNAH,dah leh,nah sehl,SNAH,dah MUK,tee/

- - / - - - / - / -

.i mi selmu'i lenu jersi la'ede'u

/.ee,mee sehl,MU,hee leh,nu ZHEHR,see lah,heh,deh,hu/

- - / - - / - - - / -

.iju mi na pacna .iju du'erda'o

/.ee,zhu mee,nah PAHSH,nah .ee,zhu du,hehr,DAH,ho/

- - / - / - - - / -

.i mi damba mu'i loi xamgu sekainai loi senkai ja depkai

/.ee mee DAHM,bah mu,hee,loi KHAHM,gu seh,kai,nai loi SEHN,kah zhah DEHP,kai/

- - / - - / - - / - - / - - / -

.i mi gunta le cevypro ki'u le cevmu'i .aicai

/.ee mee GUN,tah leh SHEHV,uh,pro kee,hu,leh shehv,MU,hee .ai,shai/

- - / - - / - - / - - / - - /

.i ganai mi ralte .ai le mukti noika selsi'a kei gi'e ka curve

/.ee gah,nai,mee RAHL,teh .ai leh MUK,tee,noi,kah,sehl,SEE,hah kei gee,heh kah SHUR,veh/

- / - - / - - - / - - / - - - / -

gi mi vreta sekai loi papkai je smakai ca lenu mi morsi

/gee,mee VREH,tah seh,kai loi PAHP,kai zheh SMAH,kai shah leh,nu mee MOR,see/

- / - - - / - - / - - / - - / -.

.i loi rolremzda ba xagmau ri'a

/.ee,loi rol,REHM,zdah bah KHAHG,mau ree,hah/

- - / - - / - - /

le nu pa prenu noi selckasu gi'e xramu'e

/leh,nu pah PREH,nu noi,sehl,SHKAH,su gee,heh,khrah,MU,heh/

- - - / - - / - - / -

bapu troci sepi'o ro leri vrikai

/bah,pu TRO,shee seh,pee,ho ro leh,ree VREE,kai/

- - / - - / - - / -

lenu snada le na selsnada ke tarci

/leh,nu SNAH,dah leh,nah,sehl,SNAH,dah keh TAHR,shee/

- - / - - - / - - / -

I'm rather proud of where I was able to obtain both pseudo-waltz 9/8 tempo, and some nice alliteration effects, as in line 12 (.i mi gunta...). Lojban's tendency towards more syllables than English occasionally forced the rhythm to be a little strained; there are places where three syllables must be said in one beat. I believe this happens quite a lot in song translations, though, and sometimes even in the original songs.

Translation

le mivmu'i the quest .ai mi senva le na se senva ke traji (Intention!) I am-a-dreamer about the not-dreamable superlatives. .ije damba le na seldamba ke traji And fighter against not-combatable superlatives. .ije renvi le drikai na selrenvi And survivor of sorrowful non-survivables. .ije virklama le virnu na se darsi And brave-goer to the brave-not-dared (places). .ije drari'a le na draselri'a ke traji And corrector of the not-correctable superlatives. .ije curve je darno ke prami And pure -and-afar-type-of-lover. .ije troci se pi'o le dusta'i ke birka And attemptor using the excessively-tired-type-of-arms(s). .ije snada le na selsnada mukti And achiever of not achievable goals. .i mi selmu'i lenu jersi la'ede'u I am motivated by states of pursuing the referents of these sentences. .iju mi na pacna .iju du'erda'o Whether I not-hope-for. Whether excessively far. .i mi damba mu'i loi xamgu sekainai loi senkai ja depkai I fight motivated by the good, (the fighting) characterized-not-by Doubt-or-Pause. .i mi gunta le cevypro ki'u le cevmu'i .aicai I attack the godly-opponent justified-by the godly-motive. (Of course I will!) .i ganai mi ralte .ai le mukti noi ka selsi'a kei gi'e ka curve If I retain (Certainly, I will!) the motive which is incidentally characterized by the property of (its) being esteemed as well as pure, gi mi vreta sekai loi papkai je smakai ca lenu mi morsi then I rest, characterized by peace and quietness, at-the-time-of the-event-of I die. .i loi rolremzda ba xagmau ri'a The world of man's home will be-better, because lenu pa prenu noi selckasu gi'e xramu'e acts of one-person who, (he/she) incidentally (being) ridiculed and much-injured, bapu troci sepi'o ro leri vrikai (he) will have attempted, using all of his/her bravery, lenu snada le na selsnada ke tarci acts of achieving the not-achievable star(s).

There are several grammatically unnecessary "ke"s inserted to preserve Lojban's stress rules. These, and including elidable terminators like "ku" and "kei" when otherwise unnecessary, will probably be a useful bit of 'poetic license' that is perfectly grammatical. In the next example, the normally elidable number terminator "boi" is used for this purpose.

'99 Bottles of Beer'

The following is taken verbatim from Lesson 3 of the draft textbook, and uses only vocabulary and grammar taught up to that point. Not great literature, but we have only 300 words and less than 1/6 of the grammar available to use at that point, yet the translation comes out as desired.

A SONG ACTIVITY

We get to do something different at this point. We will practice numbers, abstraction, and pronunciation, by singing a Lojban translation of a familiar song:

le sosoboi dacti cu botpi le birje .i le sosoboi botpi cu galtu .i nu pa le botpi cu farlu le loldi .i le bitmu cu ralte sobiboi le botpi

The song is translated in the answer key in the back of the book, in case the instructor wants to use this as a group or individual exercise. The elidable "ku"s and "kei"s have been omitted for the sake of the rhythm, whereas some of the "boi"s, all unnecessary, seem to help that rhythm.

You will find, of course, that the translation is not identical to the English, but is close enough that you will be able to identify the song and its tune. When the class knows what the song means, it can then be sung as a group pronunciation exercise, with a little quick thinking on your numbers necessary in order to do later verses.

Note the use of the abstraction as an observative bridi. This is a fairly unusual occurrence; it would be hard to find a better or more appropriate example of when it is useful.

[I - You should have pre-written the song in large print on a board so you can talk about the translation if needed, and so you can point to lines as they are sung.

After a couple of verses, you can speed up the activity and make it more challenging by having more than one bottle fall. Just say (or change on the board):

xa le botpi cu farlu

and indicate that they are to continue. If necessary, help them out by writing in numerals (not text), the new number of bottles. Pre-plan the numbers to be subtracted so that you use all of the digits, and have the answers in front of you so you don't make a mistake. It is a good idea to have rehearsed this one with your partner.]

Translation of the Activity Song

'Ninety-Nine Bottles of Beer on the Wall' le sosoboi dacti cu botpi le birje "The ninety-nine things are-bottles containing beer." .i le sosoboi botpi cu galtu "The ninety-nine bottles are high." .i nu pa le botpi cu farlu le loldi .i le bitmu cu ralte sobiboi le botpi "The wall retains ninety-eight of the bottles."

Pronunciation and Phrasing Guide

le sosoboi dacti cu botpi le birje

/leh so,so,boi DAHSH,tee shu BOT,pee leh BEER,zheh/

- / - - / - - / - - / -

.i le sosoboi botpi cu galtu

/.ee leh so,so,boi BOT,pee shu GAHL,tu/

- - / - - / - - / -

.i nu pa le botpi cu farlu le loldi

/.ee nu pah leh BOT,pee shu FAHR,lu leh LOL,dee/

- / - - / - - / - - / -

.i le bitmu cu ralte sobiboi le botpi

/.ee leh BEET,mu shu RAHL,teh so,bee,boi leh BOT,pee.

- - / - - / - - / - - / -

As you can see, the rhythm came out perfect, and the last line even emphasizes the digit which changes. Try it!

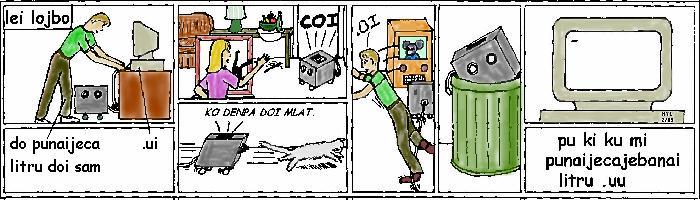

lei lojbo

Bob: mi ba te cmene do zo sam.

I will be-who-calls-by-name you 'Sam'.

.i mu'i bo le nu zo sam. rafsi zo skami

Because (motivational) the-state-of 'Sam' is-the-affix-for 'skami' (computer).

"I will call you 'Sam', since 'Sam' is the affix for the Lojban word for 'computer'."

Sam: mi skami gi'e se cmene le rafsi be zo skami

I <compute-(logical AND)-{am-named the affix of 'skami'}>.

.i .ua mi jimpe loi cmene

(Discovery!) I understand the-joint-mass-of names.

"I'm a computer, and am named the affix for the Lojban word for 'computer'. Wow! I understand names."

Nora: mi nitcu lei zbabu le nu lumci ti

I need the-specific-mass-of-soap-I-have-in-mind for-purpose the-act-of washing-this.

.i ra zvati ma

The referent of the earlier sumti (the soap) is-at where?

"I need the soap to wash this. Where is it?"

Sam: .ue zo .bab. rafsi zo zbabu

(Surprise!) 'bab' is the affix for 'zbabu'.

"Oh! 'bab' is the affix for the Lojban word for 'soap'."

Sam: la bab. zvati ti

The-one-called-'bab' is at this-here-place.

.i ko pilno la bab.

(Imperative you) Use the-one-called-'bab'.

"'bab' is here. Use him!"

Nora: .ui la sam. drani

(Happiness!) Sam is-correct.

.i mi ba pilno do doi bab. le nu lumci ti

I will use you (Vocative: O Bob) for-purpose the-act-of-washing this.

"Sam's right. I'll use you to wash this."

Nora: do prije doi skami

"You are-wise (Vocative: O computer)."

Bob: mi cfipu

"I'm confused."

Sam: .e'e cu'i

(Decision - modified as indifferently positive/negative = Indecision)

.i zo .noras. rafsi ma

"'noras' is-the-affix of what (Lojban word)?"

The joke should be obvious in this case. Our friendly computer has generalized from a single case, as he has done in previous strips. Nora's poetic streak has allowed her to be the beneficiary of this supra-logical generalization, instead of the victim she usually is.

Lojban names (as opposed to Lojbanized non-Lojban names) will probably be made from words and rafsi in just this manner: 'Lojban' itself is such a name. There are no conventions to distinguish Lojbanized non-Lojban names from coined-in-Lojban names - a name is simply what is used to label something; the etymology of a name, like most word etymologies, is interesting and sometimes informative, but is not generally vital (or even relevant) to communications. Lojban uses word-building to allow such etymology to serve as a clue to a listener who doesn't know the word; this hopefully permits greater power to express new concepts.

Among other interesting grammar aspects in this strip are the changing meanings of "ti". Like its corresponding English word "this", "ti" can change meanings as often as several times in a sentence. Its fellow demonstratives "ta" and "tu" also can vary. These 'pronouns' mean only what you want them to at the time you use them - the attachment of 'pronoun' to referent does not remained fixed as it does for "ko'a" and its free variable relatives and "da" and its bound variable relatives.

"ra" and its relatives also vary as the sentence develops. These are the 'back-counting' variables. "ri" refers to the immediate preceding sumti; "ra" to an earlier but nearby sumti; "ru" to a relatively far back sumti. In the sentence using "ra" in the comic, we could not use "ri" since it would refer to the 'le nu ...' sumti at the end of the previous sentence. Back-counting from within a sumti cannot refer the sumti itself: "le nu ri xamgu" is not self- referential; the "ri" does not count the "le" of which it is a sub-part.

When you need to hold onto a back-reference, you can assign it to a "ko'a"-series variable with "goi":

mi nelci ri goi ko'a . i la Noras. nelci ko'a

If "ri" were not assigned to "ko'a", you could not tell the referent of "ko'a". If you used "ri" again, it would refer to "la noras."

There is debate as to whether other pro-sumti should be counted: Does "mi nelci ri" say that I am fond of myself, or of some earlier sumti referent? I (Bob) favor ignoring simple pro-sumti in back-counting for pragmatic reasons: it wastes the counting access to other sumti. The counting is harder but more useful. This is a debate dating from earlier versions of the language (where "ko'a" and "ri" usages used the same set of words); the question will probably be settled based on usage by the first speakers in the next couple of months.

In the first caption, .i mu'i bo is used to motivationally connect the second sentence to the first. The structure to connect two sentences is, of course ".i". But if you want to add a causal (or any modal) connective (like "mu'i" to tie the two sentences together, you need something to separate the "mu'i" from the main sentence. Otherwise, it will be taken as a modal sumti tag. From our caption for example, if the "bo" were omitted, "mu'i" would slurp up "zoi .sam." making the caption translate as:

I will be-who-calls-by-name you 'Sam'. Because (motivational) of 'Sam' (something) is-the-affix-for 'skami' (computer). "I will call you 'Sam'. Because of 'Sam', something is the affix for the Lojban word for 'computer'."

This isn't what you want.

The LK8 strip is repeated, now that you know how the names came about:

Bob attaches a portable 'robot' peripheral to 'Sam' the computer. He uses a complex tense to say:

do punaijeca litru doi sam. do <({pu nai} je {ca}) litru> <doi sam.> "You past-not-(logical AND)-present travel. Vocative: O Sam. "You couldn't-and-now-can travel, O Sam".

Sam is happy about this (Will a computer that understands Lojban be able to use emotional indicators?):

.ui (Attitudinal indicator of happiness)

Sam causes Nora to drop her paint brush by surprising her:

coi "Greetings!" chases the cat:

ko denpa doi lat. "(Imperative You) Wait. Vocative: O Lat." "lat" is the rafsi for "mlatu" (x1 is a cat). "Wait, O Cat! "

and causes Bob to trip while watching cartoons on television (what else would a mobile computer do?) Bob complains:

.oi "(Attitudinal indicator of complaint)"

and the robot ends up in the garbage can. Sam, in self-pity, uses an even more complex tense to say:

pu ki ku mi punaijecajebanai litru {pu ki ku} {mi <{pu nai} je {ca} je {ba nai}> litru} "Relative to a previous reference time: I <past-not-(logical AND)-present-(logical AND)-future-not> travel. (Sorrow/regret!)" "At some (the) previous time, I couldn't-and-now-could-and-then-couldn't-in-the-future travel. Oooh!".

"ki" resets the space-time reference point (the narrative time) to the tense it is attached to, in this case an unspecified but obvious-from-context time in the past. The remainder of the expression then is expressed from the point of view of that time. We do something like this with complex tenses in English, such as in:

"She will be at work by 7AM. She had better have gotten up early."

The second sentence, expressed in the past tense, nonetheless is probably in the future of the speaker; the "had better" is one irregular way to put the reference time to that of the previous sentence. Compare with:

"She will be at work by 7AM. She got up early." "She will be at work by 7AM. She has gotten up early." "She will be at work by 7AM. She had gotten up early."

Each of these conveys a slightly (and perhaps subtly) different relationship between the time of expression, the time of arriving at work, and the time of getting up. The relative time-frame expressed by succeeding sentences will also vary depending on which of these forms is used.

By putting the attitudinal after "litru", the implication is that the travelling is the source of the regret, rather than the whole sentence. Attitudinals attach to the previous word (or structure - if the word is a terminator of a structure), unless at the beginning of the sentence, where it modifies the whole sentence, or unless preceded by "fu'e" which causes indicator scope to the right until marked, even across sentence boundaries. This latter may not be a truly 'natural' usage; the assumption is that emotions expressed as indicators are somewhat spontaneous, and that true 'forethought' is unlikely. However, discursives such as 'On the other hand' and 'However' are also expressed as indicators, so that the possible usage for emotional expression is a side effect. (It is useful for ritualistic and poetic expressions of emotion, and I used "fu'e" in the Lord's Prayer translation.

As indicated in LK8, the humor derives from the 'natural' use of the complexity of the tense by our all-too-literal computer. In actuality, tenses of this complexity will be uncommon in Lojban. Remember, of course, that tense is optional in Lojban in the first place. Lojban 'tense' also can include location, and it is permitted to inflect Lojban bridi with causal, comparative, and modal operators using the grammar of tense, such that they act like a cross between a tense and an English adverb.

I (Bob) spent a lot of time developing a systematic tense approach that treats time and space as equally as possible (allowing straightforward discussion of relativity concepts), while allowing the forms used in common conversations to simplify down to their past Lojban usage. I used inputs from John Parks-Clifford, whose specialty is tense logic, and he has reviewed the current design. Only usage will determine whether some of the more esoteric forms are worth having.

The design is both simple and complex. It is simple from the standpoint that all structures are set up to follow a single pattern so that it is easy to determine what pieces of a complex tense expression mean, and the proper order of terms. The result is that our tense design is grammatically unambiguous under the LALR1 algorithm, like the rest of the language. Previous language versions did not define the structure of tense compounds, and I found them to be a major area of ambiguity in grammar as well as inadequately defined.

The tense system is complex in terms of the power involved in such a design, and the number of rules and words needed to express and explain it (tense-related rules constitute about 15% of the grammar). If pc hadn't convinced me that English tense expressions are among the most convoluted and hard to understand parts of the language, I would evaluate my own design as using a steamroller to squash an ant. As it is, there will be a lot of the structure that will be little used except by physicists and philosophers. So, you learn it and possibly forget it - until you run across a situation like the one in the comic, when it is both clear and elegant.

Letters and Responses

Dave Cortesi was one of those who reviewed the section of the draft grammar description and cmavo list that I produced late last year. His comments were almost embarrassingly complimentary, but he urged me to print them anyway.

Dave Cortesi on Lojban's Design

Let me say, man, I am IMPRESSED. There is one hell of a lot of high-quality engineering visible in this work. You should take great pride in how much you've accomplished. Sure, lots of the ideas and work came from others, but you have done an amazing job of organizing and coordinating a huge quantity of very, very sophisticated stuff.

There is an interesting contrast here. Jim Brown's Loglan-1 was written in such an articulate, charming way (as is all his work) that it sold me totally, and I set out to learn the language on my own. I well remember the many hours of extremely frustrating labor that followed until I gave up. And of course over the following years we found out the language of Loglan-1 wasn't anywhere near done.

Now here we have these very dense, not very charming, engineering notes on the design of Lojban. I can't say for sure yet, but it looks to me as if this language really is there to be learned.

I guess if you can't have both good engineering and good writing then the Lojban effort at least did the more important thing first, which is to really get the design finished.

That doesn't let you off the hook, though; I still insist you have to rewrite that summary.

Bob responds:

Dave is a professional writer, with books and columns under his belt, so I take his comments seriously. The consensus among the reviewers was that, from what I had finished, it was clear that the language was done and ready to be taught (hence our current classes). The description, however, was written as a design specification - and my writing experience outside these pages is limited to writing government system specifications. I'm good at that, but what is needed in a specification is detail and accuracy, and convincing the reader that the design is well thought out and complete. Dave's comments show that Lojban-as-an-engineered-language meets that standard. The grammar description, though, is so dense that it can only serve as a reference work for someone who has the basics of the language down. It then provides answers to a lot of nitty-gritty questions about how to resolve priorities of grammar rules, etc. It is also designed to be used with the machine grammar description, which is a very formal set of rules. We thus don't recommend either to anyone not willing to work at it, and possibly being familiar with computer language specifications in 'BNF' format.

The grammar description will not be revised until the textbook is done. It has thus fallen into being a little obsolete, as minor changes are made in tuning the grammar while we write the textbook. It still is a valuable document for what it covers, and the final draft version (late this year) will serve as the basis for the grammar baselining that will truly say that Lojban is DONE.

Rory Hinnen's tanru

...

I'm a manager in a fast food restaurant here in California, so when you suggested you want lujvo based on what we deal with, as a joke I started messing with the once-uniquely-American concept of fast food.

sutsabdja is of course what you get when you go to any McDonalds. Not necessarily quickly made, or even fresh, but theoretically served fast. Probably this is what most people have in mind when they think of fast food.

sutyjupydja would be microwaveable food. sutryzbadja would be the corporate ideal (I refuse the concept that fast food is truly "cooked").

This leads to the customers' ideal of sutkemjupsabdja, food that is made and served quickly.

The decor of said establishments encourage sutctidja (or in English, "suicide"), which could result in be'ucro. But then that might be from slabu (slasutsabdja) sutsabdja, too.

That's not bad, actually. Compared to the English "Fast food" (two syllables, rather difficult to say because of the sibilants), sutsabdja has only one more syllable and seems to be just as fast. In terms of written space, they're equal (I'm counting the space as an active letter - although one could write fastfood, the reader would probably regard it as an error).

Bob responds:

The tanru and lujvo are quite good and entertainingly presented; it is clear that Roy is attempting to make fine distinctions with his various words, and the Lojban conveys those distinctions nicely. This is one of my favorite aspects of Lojban - thinking about what exactly you want to say, and expressing it concisely and effectively.

Doug Loss Responds to my JL7 Comments

First, thanks for the comments on my tanru attempts. I now realize that I got my ordering mixed up. I think this was primarily because I remember (whether accurately or not I don't know) that metaphors used to make CPXs in Loglan weren't required to fit into any specific pattern. I therefore didn't try to do so. I also tried to be aware of the place structure of the words I used, and when filling in the place structure would get at what I wanted the word to mean, to list the gismu in my prospective tanru in that order.

I therefore concur on the word tadsmadycfi for SF. And your penpe'i or penpenmi look good to me for seminar." As for the schwa/"r" hyphen question, I guess I mostly want to not have too long strings of either vowels or consonants. (Did the word order in that last sentence betray any of my PA Dutch heritage? It doesn't look quite right to me, but I don't know why.) I noticed the problem more often with "r" hyphens in the middle of consonant strings.

When I tried translating the Lord's Prayer into Loglan about 10-11 years ago, I translated "daily bread" as "that which we need for life each day." As I recall, there was a word in L4&5 for "necessities of life." It seemed that this was what was meant by the (metaphorical) "bread." For what it's worth.

I've been thinking about Jamie Bechtel's tanru and would like to take a crack at 3 of them.

You were correct in your comments on his attempt at "white noise," but your cunso dirce or blabi dirce don't get at the concept either, I'm afraid. I'm pretty sure this is the correct definition of white noise, although it wouldn't hurt to check with an audio engineer: sound with equal energy at all frequencies, to the limit of the transducer. This isn't random at all.

To get at that definition, I made "frequency" as slilu parbi, which collapses nicely to sliparbi. Then white noise becomes rolsliparbi sance (or ro sliparbi sance; I'm still not sure when and where rol can be used). There is a similar concept called black-body radiation, although I'm a bit hazy on the exact definition of the term. I think rolsliparbi dirce might be closer to that than to white noise, though.

A sieve is a specialized version of a more general concept, a filter. "Filter" (or "sieve", for that matter) might be sepli zbasu, which collapses to sepyzba or se'izba. Any place structure for this concept should include a place for the fineness of the filtering, something like "X filters Y at fineness Z." Do we get to make new place structures for tanru? They will often (I suspect) have different meanings than modified versions of the last gismu in them.

"Brachiate" is relatively easy. Assuming Jamie means to swing through trees like gibbons do, try birka dandu muvdu. This collapses to birdadmuvdu or birdadmu'u. If he means having widely spreading branches or having brachia (armlike appendages), I haven't thought about it.

The name for the mythical country seems straight- forward too. Loglandia was a cute play on the last 3 letters of "logla" and the first 3 of "land." Since "loglan" wasn't a word in Loglan, it didn't matter that this was an entirely English jape. As lojban was constructed to be a word in lojban, the name of the country should also be so constructed. So, la lojbangug. Or if that doesn't feel nice on the tongue, how about la lojbangu'es or la lojbangu'en.

I'd like to close with a few comments about Kenneth Clark's letter. First, his aversion to ambiguity is not universally shared. There are times when ambiguity is exactly the right thing to have in an utterance. And considering idioms, metaphors and cliches as the "first step in the destruction of a language" is just plain silly. Those things are what give languages their power and beauty. Let me give you an example.

I recently heard the president of Bell Atlantic say, "At Bell Atlantic, we're more than just talk." This is obviously an ambiguous statement. Idiomatically, it means that BA doesn't just talk about doing things, they actually do them. That is the way such a statement would normally be interpreted. However, the statement had been preceded by a discussion of the many aspects of BA's business, including leasing and computer repair. The statement could be taken as a summation of that discussion. This ability to have a statement mean two quite different things and to have both of the meanings be intended is quite enthralling to me.

If Mr. Clark meant to rail against unintended ambiguity, I agree. But if he meant it the way I took it, I'm afraid he's trying to do vascular surgery with an ax.

Finally, his combative attitude on the S-W test question was annoying. Lambasting whoever mentioned it next because they didn't meet his imagined standards would be counterproductive, as well as mean-spirited. If he has anything useful to say about how to run a study, he should say it, rather than pontificate about everyone else. After all, "If you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem."

Bob's notes and responses:

Your note on The Lord's Prayer seems reasonable to me. My attempt aimed at a literal translation, partly to show just how complex the logical structure is, and partly to show some of the problems with Lojban translation. We also wrote it in a couple of hours during a windy picnic, without really striving for 'art'. My main concern, of course, is that religious and political materials are so often controversial, that I wanted to minimize interjecting my personal interpretations. I believe, by the way, that any valid translation of biblical materials must be from the oldest sources, and bearing in mind the cultures of the biblical times. I by no means have the expertise in either the languages or culture to attempt a scholarly defensible effort.

Your definition of 'white noise' is good, but I'm not sure that your tanru captures it - you omit the critical feature of 'equal' (which is a major distinction from black-body radiation, which is a non-equal distribution). White noise isn't of course exactly equal at all energies, although that is the goal; it also isn't necessarily (or even usually) a 'sound'. The nature of any variations in white noise from equal distribution is based on chance, and this was the feature I used for my tanru. cunso conveys the concept of 'chance' as much as of 'randomness'. Perhaps I need cunso dunli se dirce. (I should have included the "se" in my original tanru; without it, you have the white noise generator, not the radiation.) Note that slilu has frequency built into the place structure

"ro" and other numbers/quantifiers cannot directly be used in tanru; the result, if grammatical, is one or more sumti, and the quantifiers always have scope over the entire tanru. You can use quantifiers in lujvo, however, as if they worked in tanru. Thus, ro te slilu dirce would be a sumti meaning "all which are frequency radiating", but rolterslidi'e can mean "all-frequency radiation". To use quantifiers in tanru, you need a suffix cmavo such as the cardinal suffix "mei" or the ordinal suffix "moi", which turn the quantifier into the grammatical equivalent of a brivla. Thus, a good compromise tanru (and lujvo) for white noise might be te slilu romei dunli se dirce, or tersliroldu'i seldi'e - note the suffix cmavo can't be retained in the lujvo given our current rafsi set.

tanru have the place structure of the last term of the set ALWAYS. A lujvo can, and usually does, vary from this in some way. In tanru, you can attach sumti to each of the tanru element brivla using "be" and "bei", which you obviously cannot with lujvo. Thus a tanru like sepli zbasu has the place structure of zbasu. But, more completely the full bridi translates as:

x1 <(apart-from y2) type-of (makes/builds)> x2 out of x3

where y2 is the 2nd place of sepli. x2 is obviously the filter product, and x3 the source material. A similar tanru with a different place structure (and therefore emphasis) would be sepri'a (sepli rinka), or, emphasizing the tool or apparatus nature as opposed to the operator of the equipment: sepli rinka tutci, sepli zbasu tutci, sepli rinka cabra, sepli zbasu tutci. All validly convey aspects of 'filter', though none convey the place structure you want.

To clearly get such a place structure, you need to find a tanru for the concept you want to include, and add that into the tanru, or as a separate element of the lujvo, or as a modal addition onto a place structure that doesn't include it. I'll skip the last for your example; it isn't necessary or efficient. I believe that you want "klesi" in your tanru: klesi sepli zbasu (cabra), giving the implicit place structure: "x1 is a <(category of y2 with property y3) (apart from z2) type-of maker> of x2 from x3". y3 is the place I think you want, which may not necessarily be a 'fineness', but is whatever property is being filtered out.

To express this place in a tanru is complicated and possibly confusing, but we can choose to define the lujvo "klese'izba" as "x1 filters x2 from x3 on property x4 (leaving x5 ?)". This captures and condenses the complex tanru structure reasonably effectively. We could have this place structure on the shorter lujvo, using the approximation and simplification properties allowed in making lujvo from tanru that allow us to drop out extraneous terms if no conflict results. I would leave the extra term in this case, though.

This type of analysis is what we will do in formalizing dictionary-standard lujvo. For 'nonce' lujvo, you can be looser in your analysis, provided that the understanding of your listener is taken into consideration. (You can be looser about place structures in conversation than in writing, for example, since your listener can always ask about an uncertain place structure.) tanru place structures are, however, sacrosanct.

The language is a defining characteristic of 'Loglandia', so la lojbangug. seems OK to me. Better though, we could simplify the source tanru to lojbo gugde, leaving out the 'language' as self evident: la jbogug. or la lobgug. or la lo'ogug. (I prefer the first.) Alternatively, we can recognize that 'Loglandia' is not really a place with a physical territory, and use "natmi" instead of "gugde", giving possibilities such as la jbonat. or la lobnat. or la lo'onat. (Any preference - they all seem good to me?) Of course, these are OK when used within the community that knows the language - we still need an English cognate word for the normal usage, which is in simple English examples for non-Lojbanists or new Lojbanists. The Lesson 1 enclosure has my solution, which pc liked as well: 'Lojbanistan'. The name conveys an exotic non-European nature while honoring the little seen contribution of Hindi/Urdu to Lojban. My only concern was based on the possibility that people would attach political significance to anything sounding like 'Afghanistan', given events of the last 10 years (none is intended, of course). I suspect that the connotations of that country name are both cultural and temporary.

On your last point, I agree that ambiguity (semantic, at least) and metaphor are vital and probably unavoidable in a 'real' language. Lojban offers the opportunity of minimizing or possibly avoiding such ambiguity WHEN DESIRED, while retaining its availability when appropriate. Lojban usage will strongly vary among people. Contrary to any implications in lei lojbo, I am prone to using tanru, sometimes colorful ones. Nora, on the other hand, avoids using tanru or qualifies them, using "be" and "bei" to specify sumti wherever she can. Nora obviously prefers a less ambiguous language. There is room in Lojbanistan/la jbonat. for both points of view. The balance between ambiguity and specificity that will evolve in Lojban usage sounds like a great linguistics research subject - showing that Lojban's research usefulness is not limited to Sapir- Whorf.

Till next issue: co'o lojbo